The Trick to Getting Ensemble Movies Right

Originally published on TheScriptLab.com

Every movie and TV show has a cast of characters of varying importance. And while the vast majority of TV shows these days feature ensembles, it’s rare to see a movie that does the same.

The key difference is fundamental to each medium.

In TV shows, there are an endless number of possible episodes and stories, meaning that the writers have plenty of time to develop and expand their characters’ personalities. There’s no need to reveal everything in the first episode, because that would ruin the fun for the following seasons.

Film, on the other hand, is limited. Writers have two, maybe two-and-a-half, hours to introduce all the necessary characters, establish the setting, get down to business with the plot, and tell a full, complete story. Unless you’re working with a franchise, which, quite frankly, isn’t the norm, there usually isn’t enough room for an entire ensemble of characters.

But, there are instances in which filmmakers have hit the ensemble target right on the mark. The most notable is Wes Anderson, whose entire repertoire of films seems to feature successful ensembles. His most recent movie, “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” juggled no less than 13 important characters. “The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou” and “Moonrise Kingdom” both had just shy of that number.

Look carefully at Anderson’s movies and you’ll discover the key to managing an ensemble cast in a feature film — purposefully controlling how the characters are portrayed.

Anderson deftly populates his scripts with outlandish, singular characters. Some have personalities unique only to themselves (Monsieur Gustave and Steve Zissou), some are defined by their actions (Zero Moustafa and Captain Sharp), and still others are characterized by what they do or do not say (Sam, Suzy, and Eleanor Zissou).

It is in the way these characters interact with one another that makes an ensemble successful, something Anderson seems to understand more than most. He uses his characters to characterize and explain one another, and then lets the actors embody the people they’re playing to create a wholly new character.

In “The Grand Budapest Hotel,” Jude Law explains his own character, and Zero Moustafa’s, to the audience. Mr. Moustafa then explains the personality of M. Gustave who, in turn, introduces a younger Zero to all of the other characters.

No two characters are the same in a Wes Anderson movie, nor should they be in any ensemble feature.

Each character in “Moonrise Kingdom” has a dominating quality, something that makes them different from everyone else. Captain Sharp is diligent, while Scout Master Ward is disciplined. Sam is resourceful, Suzy is fierce, Mr. Bishop is quiet, and Mrs. Bishop is unaware. Even the Narrator takes on a personality in the story: wry, when everyone else is serious.

By utilizing casts of individuals who are completely different from one another, then pitting them against each other because of their personalities, Anderson is able to create huge numbers of memorable characters and fuse them together in stories that are easy to follow and come together nicely in the end.

That’s a tough line to walk, which means that ensembles movies aren’t impossible, but they are incredibly difficult to get right.

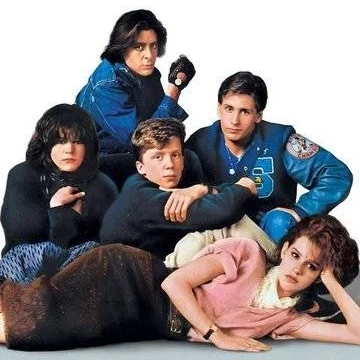

Christopher Nolan’s “Inception” features 11 characters, and “The Prestige” has seven. (His “Dark Knight” trilogy movies have even more … but it’s a franchise so it doesn’t really count.) “The Breakfast Club” has six primary characters and is barely over 90 minutes long, “The Help” includes 10, and “American Hustle” has nine. More recently, the main characters in “Spotlight” and “The Big Short” numbered about seven each.

In some cases, the individuals in an ensemble are just archetypes of familiar characters audiences will know immediately. There’s a reason the characters in “The Breakfast Club” can be easily defined by a simple moniker like “jock” or “princess” — it helps the audience understand and relate to the characters quickly, so that the film can get on to the actual point (showing how they’re all more similar than they are different). In other cases, the ensemble themselves are only an outlet for the story; the individual personalities in “Spotlight” matter far less than the story the film tells.

Either way, the key to packing a slew of characters into the same story is in the word itself: character.

Without distinctly different, oddly specific, or unparalleled personalities, your characters will blend together in the minds of the audience members. It is only when you create true “characters” that your ensembles will succeed.